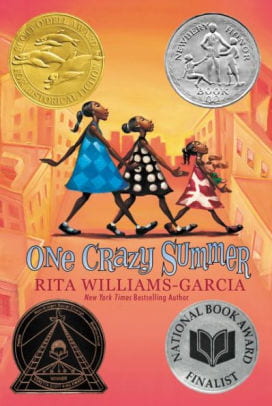

I love middle grades novels and I am used to reading the very best ones. I don’t read them as books for children, I read and enjoy them the way I do any book — because they tell good stories, because they introduce me to characters that I want to know, and because they make me think. I fall HARD for complex characters that defy an easy sorting into “good” or “bad,” which is why I could not get enough of the glorious book, One Crazy Summer by Rita Williams Garcia. Historical fiction written for a middle grade audience and set in Oakland California in 1968, One Crazy Summer offers some unique perspectives.

There are a lot of great books for young readers set during the civil rights movement: We March by Shane Evans, The Watsons go to Birmingham by Christopher Curtis, Rosa by Nikki Giovanni, Freedom on the Menu by Carole Boston Weatherford, Martin Rising by Andrea Davis Pinkney, Let the Children March by Monica Clark-Robinson. Most of these books focus on the struggle in the south, most center on non-violent resistance, and most celebrate Martin Luther King. Why is it that there are so many books about the Montgomery Bus Boycott or the March on Washington, but there are no books about one of the most important political movement in Black history — the Black Panthers? One Crazy Summer changes that.

Meet Delphine Gaither — the oldest of three and the caretaker of younger sisters Vonetta (age 9) and Fern (age 7). The girls live in Brooklyn, New York with their father and grandmother but are sent to spend “one crazy summer” with their estranged mother, Cecile, in Oakland, California. As Delphine expects, Cecile doesn’t welcome the girls with open arms. No, Delphine explains, she is “Cecile – mammal birth giver, alive, an abandoner – our mother. A statement of fact.”

Readers soon learn that Delphine is not exaggerating about Cecile. In fact, through the character of Cecile Williams-Garcia gives readers the least maternal character I have ever read in a children’s book. Nzila, as she is known to her Panter brothers and sisters, is a poet and artist. She owns a printing press that is kept in her kitchen (off limits to the Gaiter girls) where she does her art. She lives alone in a blue stucco house and sends the girls to the corner restaurant for take out Chinese food for all of their meals until Delphine, dedicated to caring for her siblings as she promised her father, begins making dinners in Cecile’s kitchen (Delphine is the only person allowed in).

The first morning the girls are sent to “The People Center” for breakfast (referencing the historic project run by the Black Panthers). Admonished not to come back until day’s end, the girls spend most of their days at the center in a children’s summer program. They steadfastly claim that they are “there for breakfast and not for revolution” but by and by they grow into new identities until one day, on an outing in San Francisco, they greet a young flower-child on the street with, “Power to the People.” Later that day, when they are watched by a shopkeeper, Delphine states, “We are citizens and we have a right to be here” before the three girls leave the store with their heads held high. It is this subtle transformation that makes the story shine. The Gaither girls are strong and spunky — they arrive that way and they leave that way — changed by their crazy summer but still firm in who they are.

But the real transformation is the character of Cecile. Through Cecile, Williams-Garcia offers a character with uncommon depth and nuance for children’s literature. Cecile is unapologetically not maternal. In fact, Delphine’s on-going criticism of Cecile seems to be preparing the reader for a major maternal awakening. Nope. That would be too predictable for this smart book. While glimpses of Cecile and Delphine’s relationship serve to humanize the character of Cecile, it is not until the end of the book, in two short pages when she tells Delphine about her traumatic past, that we fully embrace her humanity.

One Crazy Summer brims with life. It would make a wonderful class read-aloud for upper-grade elementary or a Book Club choice for the genre of historical fiction.